Communication and Dissemination Plan

This document describes the dissemination and communication plan for the COST Action “Underground4value”, including the different tools, channels and means of communication that will be implemented throughout the project duration. The plan also describes the target groups of the dissemination strategy and it outlines the key dates related to planned actions and events. It contains the main strategic and operative guide that shall govern the overall action dissemination and communication activities. These guidelines will help to ensure that relevant information is shared with appropriate audiences on a timely basis by the most effective means. The dissemination activities will be continuously monitored during the action. The main objective of the communication activities is to raise awareness about the action activities, disseminate information in a consistent and coherent manner about its results, and maximize its impacts. It will formulate criteria for the exploitation strategy. Additionally, this document is a guideline for all involved stakeholders to establish their individual dissemination/exploitation plans within their local context. This is a ‘living document’ to be updated during the Action lifespan.

An UBH knowledge repository is necessary to classify different typologies and define common standards and methodologies, to cover many different aspects (i.e. archaeology, geotechnics, history, spatial and urban planning, cultural anthropology, economics, architecture, cultural tourism).

The repository will simplify UBH related surveying and dissemination practices, by supporting different stakeholders with historical and archaeological backgrounds, integrated geophysical explorations, and surveys of the earth and subsoil resource.

It will allow simplified procedures and protocols for assessing the state of the UBH conservation, within European regulations in heritage conservation (CEN/TC 346 – Conservation of cultural property), reducing technological and financial difficulties in the data collection of underground conditions.

New emerging technologies (see WG2) such as three-dimensional (3D) computer modelling and different sensing techniques can become a primary thrust for underground heritage research and development (e.g. ‘seeing through the ground’). The WG2 explored the following tools: cameras and thermovision systems; monitoring systems

By approaching and managing UBH as a commons (WIKi-community) it is possible to improve collaboration among scientists and reducing costs for sharing knowledge.

The main reference for promoting a UBH sustainable use is the “Recommendation on the Historic Urban Landscape (HUL)”, adopted in 2011 UNESCO’s General Conference. The HUL is aa holistic approach for historic urban landscape management, which considers heritage as a social, cultural and economic asset for the urban development and aims at “…preserving the quality of the human environment, enhancing the productive and sustainable use of urban spaces, while recognising their dynamic character, and promoting social and functional diversity” (UNESCO, 2011).

Topics such as cultural heritage, urban and rural regeneration, and sustainable tourism are strategic opportunities at neighbourhood, urban and regional levels, if developed in a context of community engagement, with more effective coalitions of ‘actors’ supported by structures that encourage collaborative relationships.

One challenge is the application of two community management tools – such as Strategic Stakeholder Dialogue (SSD) (Van Tulder et al 2004) and Transition Management (TM) (Kemp at al. 2005), and their integration into a new tool, the Strategic Transition Management (STM), based on local communities’ experiments and empowerment, and a multi-level strategic dialogue (e.g. Living Labs).

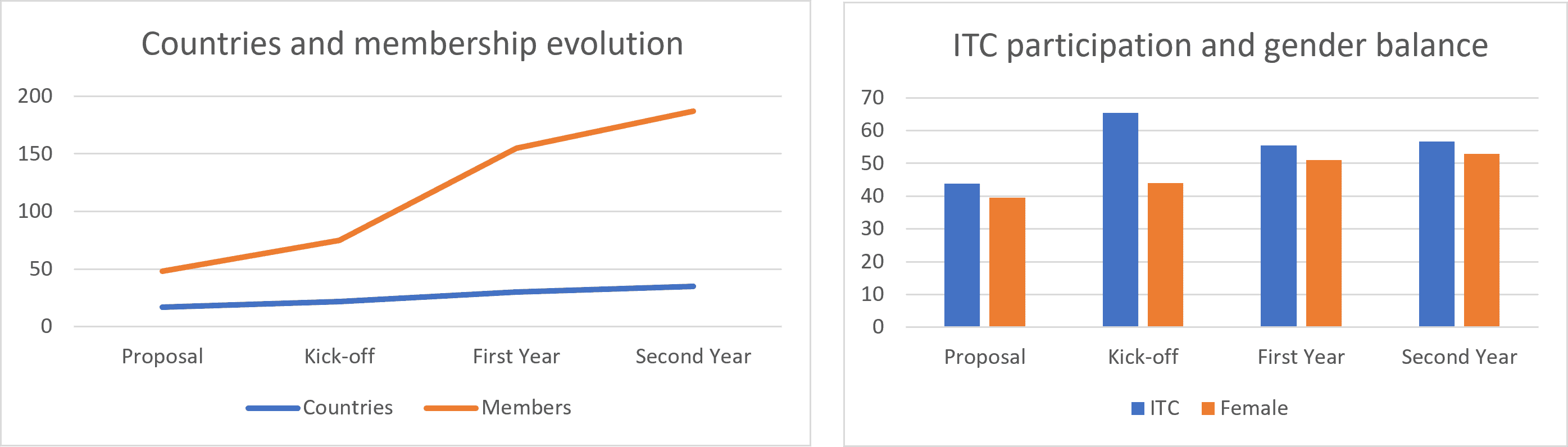

Passing from the initial 49 co-proposers (November 2018) to 85 at the kick-off (April 2019), to 155 participants at the end of the first year (April 2020), and to 187 at the end of second annual period (October 2021), participation grew almost four times in the first two years.

The ITC participation was very high since beginning, with 41%, and went up to 51% at the kick off meeting, to 57% at the end of second period.

Early Career Investigators rate increased from the initial 10% in the proposal to 21% at the end of the first period. Since the second period, COST accounts for Young Researchers (<40 yrs old), which at October 2021 are 68, representing 36% of the total.

The female participation rate in the MC passed from 38,8% (proposal) to 44% at the Action kick-off, to 51% at the end of the first year, and finally to 53% end of the second period. The female participation at the meetings (Ancona, Naples, Murcia, and Lisbon) was about 51%

Action Chair: Giuseppe Pace

Action Vice Chair: Susana Martinez-Rodriguez

Science Communication Manager: Tony Cassar

Grant Holder Manager: Patricia Sclafani

Webmaster: Olga Lo Presti

Webdesign by Digitisation Department at